The Trouble with Anti-Aliasing (updated)

- by: Take Vos

- date: 24 Oct 2022

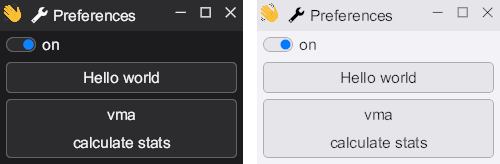

When I was working on the font rendering in HikoGUI I found an issue where the text looked to have a different weight between the light and dark mode of my application.

The rendering above was done inside the SDF (signed distance field) fragment-shader completely in linear-RGB color space. And as you see the weight of the text in light-mode is too thin, and the weight in dark-mode is too bold.

So why is this happening? According to many articles about font rendering this is happening because we did the compositing in a gamma color space. However we did actually render is linear color space, so we have done this correct.

Other articles talk about that fonts are designed to be black-on-white and you should use stem-darkening. Which is weird because the stem darking is supposed to be done on the, already designed for, black-on-white text.

So I decided to investigate what is really happening here, and in short I found that when anti-aliasing our eyes expect a perceptional uniform gradient, which does not happen when mixing the foreground and background color in a linear-RGB space.

Doing the calculation

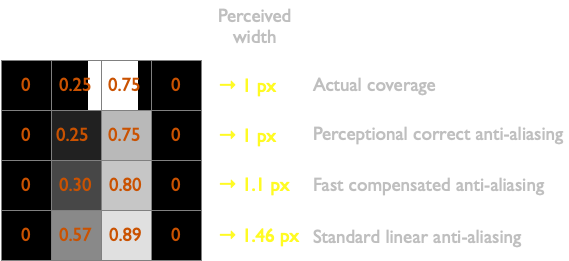

In this chapter I will show why a \(1\) pixel wide white line and a black background will visual look like a \(1.46\) pixel wide line after anti-aliasing in linear-RGB color space.

For this example we will draw a one pixel wide vertical line with its center at \(x = 1.75\). The line is white on a black background, which means that the alpha of a pixel can be directly translated into linear luminance values.

But since our eyes do not perceive luminance values as linear we will need to convert these values to lightness values using the formula from CIE L*a*b* 1976. I filled in \(Y_n = 1.0\) into the formula and normalized \(L\) between \(0.0\) and \(1.0\) to make it easier to work with:

\[L = \begin{cases} 1.16 \cdot \sqrt[3]{Y} - 0.16 & \text{if } Y > 0.00885\\ \\ 9.03297 \cdot Y & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}\]In the table below you can see a horizontal strip of 4 pixels, with the linear luminance values and the perceptional uniform lightness values. As you see our intended vertical line is \(1\) pixel wide. But after we calculated what a human eye really perceives we find that the line is visually \(1.46\) pixels wide.

Don’t: anti-alias in the sRGB color space

At this point you may think, okay… anti-alias instead in the sRGB color space. The sRGB’s transfer function (gamma), by design, already approximates the perceived lightness.

This will actually work, up to a point. Many font rendering engines do this, probably after having experimented with linear anti-aliasing and not getting the desired results. And even image editors used to compose in a similar non-linear color spaces in the past.

However instead of a uniform gradient between the foreground and the background the colors may get seriously distorted. When using red on a green background for example the gradient passes into dark brown colors as shown in the image below.

Do: anti-alias in CIE L*a*b* color space

So we can’t blend in either a linear-RGB space, nor in a uniform-RGB space. What we would like is a color space that allows us to blend the perceptional uniform lightness together with linear colors.

The CIE L*a*b* color space has a perceptional uniform lightness in one axis and a separate perceptional uniform color plane. The CIE L*a*b* color space may be a valid color space to do anti-aliasing in, but it is computational expensive.

Do: Properly calculate coverage for sub-pixels

We sample the signed distance from the center over each sub-pixel. Since we only have a distance and not an angle, we measure the coverage of a plane and a circle. The SDF measures the plane’s edge from the centre of the circle, when the signed-distance is negative the plane intersects with the centre of the circle, while positive it doesn’t.

The circle’s area should match the area of the pixel which is 1.0 x 1.0 = 1.0, this makes: r = sqrt(1/π) = 0.5641895835.

d = signed distance

r = radius of sample circle

x = d / r (-1 <= x <= 1)

f(x) = (1/π) * (acos(x) − xsqrt(1 - xx))

Perceptional uniform anti-aliasing

Do: Convert coverage to alpha with perceptional compensation

Lets try something cheaper.

We would like to be able to use the following GPU features:

- Fixed-function Linear alpha blending

- Per color channel alpha blending (can be used for sub-pixel anti-aliasing).

- Don’t read the destination frame-buffer in the shader.

If we want to use the alpha channel, we need to convert the coverage value to the alpha value by looking at the perceptional lightness of the foreground and background color.

The following formulas are used to convert a coverage value to an alpha value when both the background and foreground colors are known:

| variable | description |

|---|---|

| \(c\) | coverage; The amount a pixel is covered by the glyph. |

| \(F\) | foreground luminance (linear). |

| \(B\) | background luminance (linear). |

| \(T\) | target luminance (linear). |

| \(\bar{F}\) | foreground lightness (perceptional). |

| \(\bar{B}\) | background lightness (perceptional). |

| \(\bar{T}\) | target lightness (perceptional). |

| \(a\) | perceptional compensated alpha value. |

However we do not know what the background color of the text is, So instead we expect that the text will be contrasting with the background.

After filling in \(F = 0, B = 1)) and ((F = 1, B = 0\) in the formulas above and simplify it we get two coverage-to-alpha formulas.

Then we linear interpolate mix() between the coverage-to-alpha formulas for

black-on-white and white-on-black, by the perceptional uniform foreground lightness.

| variable | description |

|---|---|

| \(c\) | coverage; The amount a pixel is covered by the glyph. |

| \(\bar{F}\) | foreground lightness (perceptional). |

| \(a_w\) | alpha for white text on black background. |

| \(a_b\) | alpha for black text on white background. |

| \(a\) | perceptional compensated alpha value. |

In GLSL this is simply:

float coverage_to_alpha(float coverage, float sqrt_foreground)

{

float coverage_sq = coverage * coverage;

float coverage_2 = coverage + coverage;

return mix(coverage_2 - coverage_sq, coverage_sq, sqrt_foreground);

}

Terms

Linear-sRGB color space

Linear-sRGB is an inaccurate term describing a color space based on the sRGB color primaries and white point, but with a linear transfer function.

The color component values have a range between \(0.0\) and \(1.0\) and are represented as floating point values. In certain cases values outside the \(0.0\) to \(1.0\) range are allowed to handle luminance values beyond \(80 cd/m^2\) for HDR, or negative values which represent colors outside the triangle of the sRGB color primaries.

This is the color space that is used inside fragment shaders on a GPU.

Luminance (Y)

The luminance is a physical linear indication of brightness.

In this paper we use the range of luminance values between \(0.0\) and \(1.0\) to be mapped linear to \(0 cd/m^2\) to \(80 cd/m^2\); which is the standard range of sRGB screen-luminance-level.

The luminance value is calculated from the linear-sRGB values as follows:

\[Y = 0.2126 * R + 0.7152 * G + 0.0722 * B\]My intuition of luminance calculations in high-gamut extended-sRGB color space is that the luminance is always positive. Since if a color outside the standard-sRGB triangle is selected at least one of the components must be a positive enough value to force the luminance to be above zero. Having only positive values is important for taking the square root, see the next section.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Relative_luminance

Lightness (L)

Lightness is the perceptual uniform indication of brightness.

In this blog post we use the range of lightness values between \(0.0\) and \(1.0\) to be mapped non-linear to \(0 cd/m^2\) to \(80 cd/m^2\). which is the standard range of sRGB screen-luminance-level.

The formula to convert luminance to CIE L*a*b* lightness value is:

\[f(t) = \begin{cases} \sqrt[3]{t} & \text{if } t > ( \frac{6}{29} )^3 \\ \frac{1}{3} ( \frac{29}{6} )^2 t + \frac{4}{29} & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}\] \[L = 1.16 f \left( \dfrac{Y}{Y_n} \right) - 0.16\]The formula below is an approximation made in 1920, which is much faster to calculate in hardware.

\[L = \sqrt{Y}\] \[Y = L * L\]